The Identity Crisis of the 60-Year-Old Intern: Why Your Career Stage Model Just Became Obsolete

- Adrian Munday

- Dec 21, 2025

- 6 min read

It's a lazy Sunday afternoon and I've just watched Robert de Niro in The Intern. De Niro plays a 70 year old widower who joins a senior intern program at a fast growing online fashion start up. So far, so Hollywood. Except the premise of the movie is that de Niro's character is a true anomaly - fitting in pretty seamlessly into a tech-oriented startup; he's mobile, sharp and socially fluent. These are the attributes people assume of a fit 40 or 50 something year old. AI-driven medical advances are creating a meaningful probability that older workers universally will have those attributes, some research suggesting this could impact some as soon as 5 years away.

If this comes to pass we're about to face a fundamental mismatch between biological possibility and social infrastructure. Understanding this gap matters because career decisions made in your 30s and 40s assume a working life that may no longer exist. The benefits of getting this right? Sustained purpose, financial security, and psychological resilience across decades you didn't plan for. The risks of getting it wrong? Identity collapse, status wounds that never heal, and the particular misery of being simultaneously experienced and irrelevant.

Unfortunately, most career advice still assumes the old trajectory: establish yourself, maintain your position, gracefully decline. Organisational psychology has studied transitions within a 40-year working life. Extend that to 55 years and the research simply breaks.

The challenge here for many is that your job title cannot be your only answer to "who are you?" The people who thrive in extended careers will be those who practised identity diversification long before they needed it. They treated reinvention as a skill to develop, not a crisis to survive.

I'm going to show you what the research actually says about successful late-life pivots, and what that research suggests is a framework for building the psychological infrastructure you'll need.

With that, let's dive in.

The Career Model That Stopped Working

Donald Super developed his career stage theory in the 1950s, dividing professional life into five neat phases: growth, exploration, establishment, maintenance, and decline. The model assumed you'd explore options until your mid-20s, establish yourself by 45, maintain your position until 65, then gracefully disengage. It was elegant, intuitive, and perfectly suited to an era when people joined companies for life and died within a decade of retirement.

That world is vanishing faster than our institutions can adapt.

In December 2024, researchers announced that treating elderly mice with a combination of oxytocin and an Alk5 inhibitor (no I didn't know what was either until I googled it) extended male lifespan by more than 70 percent, with marked improvements in agility, endurance, and memory. Both compounds are already in clinical trials for other purposes. Meanwhile, Bank of America's Breakthrough Technology Dialogue in February 2025 featured experts predicting that living well to 120 will become commonplace. Not just surviving to 120. Living well.

The labour market is already responding to earlier, subtler shifts (real-wage economics and social support structures being two). Nearly one in five Americans over 65 now participates in the workforce. The number of workers 65 and older surged 33 percent between 2015 and 2024, while the overall labour force grew by less than 9 percent. Newsweek reported in July that 51 percent of retirement-age adults now expect to work indefinitely.

This underscores the way in which the implicit contract between employer and employee has changed in my three decades across consulting and banking. The defined benefit pension that incentivised you to stay put has given way to the money purchase pension or 401(k) that follows you anywhere. The job-for-life has become the career-of-many-chapters. But our psychological models haven't caught up. We still think in terms of climbing, plateauing, and descending. The ladder metaphor persists even as the ladder itself disappears.

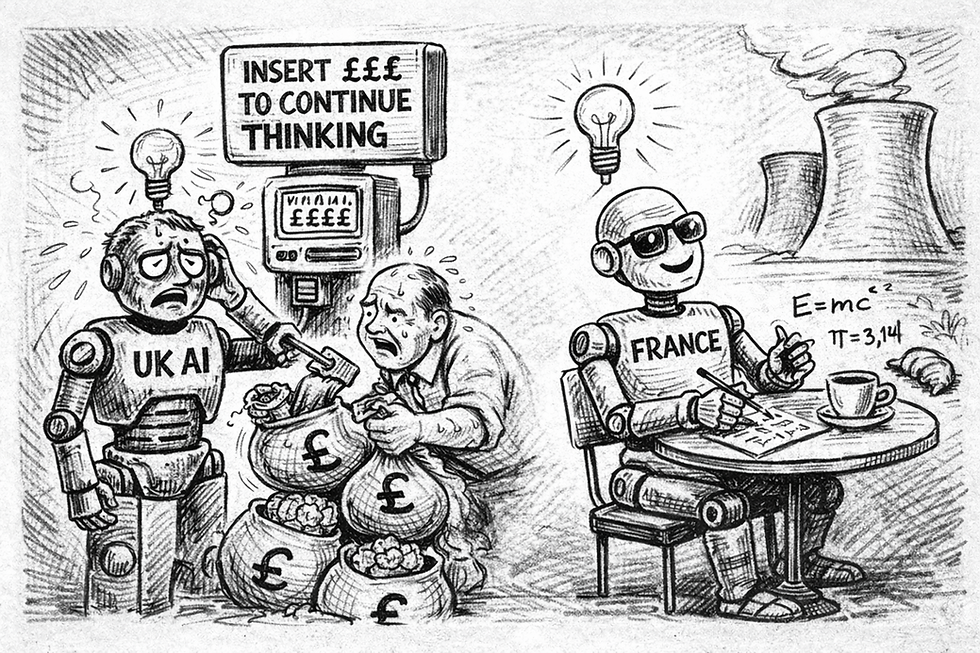

The question for me now (and perhaps it's been this way for a while) isn't whether you'll need to reinvent yourself. It's how many times. AI and its various implications adds rocket fuel to this question.

The 'Status Wound' That Becomes Key

The career literature celebrates reinvention. The TED talks feature people who pivoted at 55 and found their calling. What they rarely mention is what researchers call the "demotion effect", the psychological devastation of moving down when you've spent decades moving up. The 'status wound' that the change inflicts.

The implication of a "longevity leap" however, is that if you work until 75 or 80, you won't just face one potential reinvention. You'll face three or four. And some of those will involve starting over in domains where you have no established reputation. You'll be the grey-haired person learning Slack from someone half your age. You'll experience what I think can only be described as the mixture of humility and humiliation that comes from knowing more than everyone in the room about one thing, while knowing less than everyone about another.

Research from the Journals of Gerontology distinguishes between bridge employment and encore careers. Bridge employment extends your existing career. Encore careers involve genuine reinvention into new fields. The predictors of success in encore careers turn out to be counterintuitive: prior volunteer experience in the new sector matters more than transferable skills. People who succeed have already developed relationships and realistic expectations before they make the leap. Those who arrive with impressive CVs but no sector experience "wash out quickly because they don't have a clear idea of what day-to-day life is like."

This is the status wound in microcosm. Your experience counts for less than someone else's familiarity. Your expertise has currency only in markets that may no longer exist.

The metaphor I keep returning to is immigration. Reinventing yourself at 60 is like moving to a country where your credentials aren't recognised. You know you're qualified. Everyone can see you're qualified. But the system requires you to prove it all over again, in a language you're still learning.

Building Identity Infrastructure Before You Need It

The research on multiple identities and wellbeing points toward an answer. Studies with nearly 3,000 participants found that individuals who maintain multiple social identities and successfully integrate them show significantly higher psychological wellbeing. The key insight is that identity diversification isn't about having backup plans. It's about building a self that doesn't collapse when one pillar is removed.

A Framework for Identity Diversification:

First, the research suggests practising answering "who are you?" without mentioning your job title. If you struggle, you've identified the vulnerability. Your professional identity has colonised territory that should belong to other selves. Start reclaiming it now through deliberate investment in non-work identities.

Second, seek environments where learning is valued over knowing. PwC's 2025 Global Workforce survey found that employees with the highest levels of psychological safety are 72 percent more motivated than those who feel least safe. Psychological safety means feeling comfortable speaking up, experimenting, and learning from failure. If your current environment punishes not-knowing rather than focusing on learning, the research suggests either change it or move on.

Third, build a personal board of advisors spanning multiple generations. The research on reverse mentoring shows that intergenerational knowledge exchange benefits both parties. Senior executives who participate in reverse mentoring programmes report better decisions and stronger relationships. But the deeper benefit is normalising the experience of learning from those with less status. If you've practised it for years, it won't feel like humiliation when circumstances require it.

Fourth, create optionality through deliberate exposure. The CIPD's December 2024 research found that 41 percent of workers over 45 who haven't participated in training want to. The barrier isn't motivation. It's the fear that requesting training signals a knowledge gap that makes you vulnerable. Overcome this by treating continuous learning as a visible commitment rather than a hidden remediation.

This doesn't have to be in public either. Right now I'm quietly learning React Native to build mobile apps in the background (by hand, not using AI) to understand the mechanics of how the specific technology works. Obviously now my mother and best friend who read this blog also know.... But the point for me is that I've no idea if this will ever be directly useful in my career (likely not given AI coding trends) but it keeps my continuous learning muscle active and me using current technology stacks.

The Bottom Line

This blog was going to be about the economic cliff edge that 'longevity-jump-risk' creates in a world of AI medical advances. But it dawned on me (thanks to De Niro and Hathaway) that the people impact is much greater and more insidious.

The old career model gave us a comforting narrative: work hard, establish yourself, maintain your position, retire with dignity. The stages were predictable. The transitions were manageable. You knew where you stood on the ladder because the ladder had fixed rungs.

The new reality demands something different. Fractional work and portfolio careers have been around for a while although are not yet mainstream. But biological advances may extend your productive years far beyond anything the career theorists imagined. However social systems, employer expectations, and psychological models haven't caught up. You may have the health and capacity to work until 80, but no clear path to relevance.

The people who navigate this successfully will be those who built identity infrastructure before the crisis arrived. They diversified their sense of self. They practised learning from those with less experience. They created optionality through exposure and relationships. They treated reinvention as a skill to develop across decades, not a single pivot to survive.

Until next time, you'll find me contemplating what I'll do with an extra twenty years I hadn't planned for, hoping the answer is more interesting than "the same thing, but longer."

Comments