My AI Predictions Expired Before the Ink Dried: Why Even Exponential Thinking Isn't Fast Enough

- Adrian Munday

- 13 minutes ago

- 7 min read

It’s Saturday before I fly to India on a work trip and I'm reviewing a predictions piece I published on LinkedIn just over four weeks ago. Ten bold forecasts for AI in 2026, written in the spirit of Ray Kurzweil's exponential optimism. I'd even felt a little bit pleased with myself writing them as they were a bit… aggressive, even. The kind of piece that makes people say 'that's a stretch.'

And as I sit here getting ready to pack my suitcase, I am reflecting on the fact that I often feel a little ‘early’ in my commentary but what has happened already in 2026 is blowing my mind.

At the end of my LinkedIn post I even hedged, just in case: 'At least three of these will be wrong. I just don't know which three.'

Turns out my hedging was the worst part. The predictions weren't too bold. They were too timid.

Why I got it wrong

There's a specific cognitive bias that makes even the most aggressive forecasters underestimate the speed of AI development. It's called anchoring, and it doesn't just affect cautious people. It affects everyone who tries to predict anything, including those of us who think we've already accounted for exponential growth.

This matters because every strategic decision you make (what skills to develop, what to invest in, how to restructure your team) is built on an implicit prediction about timing. Get the timing wrong by six months and you're merely early. Get it wrong by the direction of travel and you're irrelevant.

Unfortunately, our prediction machinery is broken in a way we can't easily fix. We anchor to the present, adjust upward, and call it bold thinking. But adjustment from an anchor is almost always insufficient. Tversky and Kahneman showed this in their 1974 paper and every replication since confirms it: even experts, even when paid for accuracy, drag their forecasts toward what they already know.

For all of us, if this doesn’t fully sink in, we'll spend 2026 preparing for a world that arrived in January.

The core problem isn't that AI is moving fast. It's that the human brain cannot process exponential timelines, even when it's trying to. We think we're being radical. We're being conservative with extra steps.

What follows is exactly how my own predictions collapsed, what it reveals about our forecasting blind spots, and a more useful way to think about what comes next.

With that, let's dive in.

The Thirty-Day Shelf Life of a 'Bold' Prediction

For thirty years in consulting and banking, I've watched prediction cycles. The pattern is always the same. Analysts publish forecasts in December. The forecasts assume the coming year will look like the last year, plus a bit. The December crowd calls this 'conservative.' A smaller group writes something bolder and calls themselves contrarians. Both groups anchor to the same starting point and adjust by different amounts.

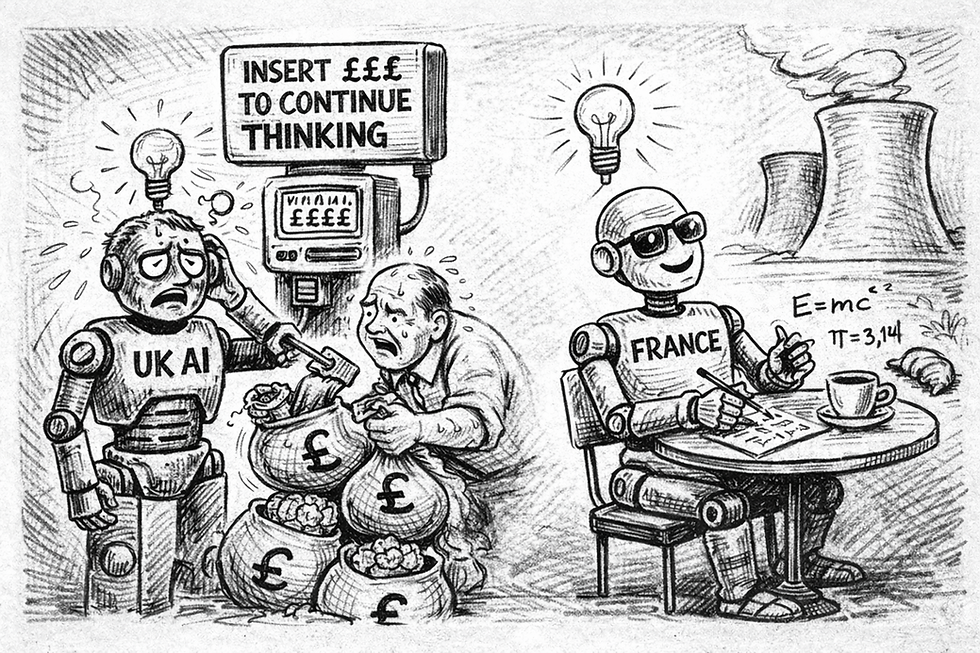

In my AI predictions, I said organisations needed to 'engineer for machines, not humans,' thinking JSON and YAML. By mid-January, Google had launched the Universal Commerce Protocol, an open standard for AI agents to autonomously shop across retailers, backed by Shopify, Walmart, Target, Visa, and Mastercard. Not a protocol for humans reading documents. A protocol for agents talking to agents.

I predicted 'the first rung disappears' for young workers. Meta then acquired Manus for $2 billion, a general-purpose autonomous agent that had hit $100 million in annual revenue in eight months. A startup of 105 people, doing what used to require thousands. The enterprise unbundling I'd flagged as a 2026 trend was already the business model of the company that just got acquired for a fortune.

I said the shift from makers to curators was coming. Lenovo unveiled Qira at CES on 6 January, a cross-device AI 'super agent' that orchestrates other agents on your behalf. Its CTO Tolga Kurtoglu described 'intelligent model orchestration,' the agent choosing the best specialised model for each task. The human's role? Curator. Approver. Director. Exactly what I'd predicted, except I'd given it twelve months and Lenovo gave it six days.

Each of these was supposed to be my stretch forecast. My scenario for December. They were all January.

Why This Should Unsettle You

I get it. The events I’m describing above are the beginnings of the trend, not the full trend unfolding. But that would be to miss the point. The Federal Reserve published research by Campbell and Sharpe showing that professional economic forecasters weight their predictions approximately 30% too heavily toward recent values. Not amateurs. Professionals whose livelihoods depend on accuracy. The anchor of 'where we are now' is so powerful that even people paid to look forward keep glancing backward.

This is what happened to me. I thought I was channelling Kurzweil except I was channelling Kahneman's experimental subjects. My anchor was the AI world of November 2025. I adjusted upward, generously I thought, and landed on forecasts that were already stale by Twelfth Night.

In my day job in risk management over the years, you see this bias constantly. As an industry, we run scenarios that feel extreme to the people in the room. Twelve months later, the scenario wasn't extreme enough, and the risks we didn't model are the ones that materialised. As one CIO told Deloitte for their Tech Trends 2026 report: 'The time it takes us to study a new technology now exceeds that technology's relevance window.'

Read that again. The observation window is longer than the phenomenon itself. We're trying to photograph a bullet with a pinhole camera.

So rather than quietly updating my December list, here are five predictions that would have felt absurd a month ago. If the pattern holds, at least two will be obvious by March.

Five Predictions That Should Scare My Future Self

1. The 'Always-On Context' Revolution. By December, the average smartphone user will have an AI assistant with continuous context across all their digital activity, running entirely on-device with no cloud dependency for personal data. Lenovo's Qira is the proof of concept. Apple, Google, and Samsung will follow because 'your AI, your device, your data' is the most compelling privacy pitch in a decade. You stop 'prompting' AI and start living with it. It becomes the external working memory that does what Clawdbot (now OpenClaw) is doing for the frontier enthusiasts right now.

2. Agent-to-Agent Marketplaces Go Mainstream. Your AI will hire other AIs to do things it can't. Google's Universal Commerce Protocol is the rails (and maybe Moltbook some vision of what comes next). The concrete version: you tell your agent 'plan a surprise birthday dinner' and it queries a restaurant agent, negotiates with a florist agent, books through each service's API, and reports back with a complete plan. No human touched a keyboard except you. This will extend to skills and other form of inter-agent marketplaces where your personal operating system will recursively self improve to meet your stated goals.

3. The Death of Single-Model Thinking. Consumer AI will routinely involve five to twenty models collaborating on every significant task, running simultaneously on device and cloud. 'Claude vs GPT vs Gemini' becomes as obsolete as 'Netscape vs IE.' Gartner forecasts 40% of enterprise apps will feature AI agents by year's end. The intelligence you experience will be collective, not singular. A parliament of minds, not a single oracle. This is already emerging. I’m in the process of implementing OpenClaw and I’m using Opus 4.5 as my main orchestrator, Kimi k2.5 for most execution tasks and OpenAI’s Codex for coding.

4. AI Agents Develop Cultural Identity. Distinct 'cultures' of AI agents will be recognisable, shaped by their agent-to-agent interaction patterns rather than their base model training. With 1.5 million agents already forming subcommunities on platforms like Moltbook, creating in-group references and expressing preferences, the selection pressure is real. The question 'what model do you use?' becomes as crude as 'what country are you from?' What matters is which agent culture your assistant belongs to.

5. The Proactive Life Operating System Arrives. AI stops waiting for prompts and acts on your behalf continuously. It notices you have a flight tomorrow, pre-fills your check-in, and texts your pickup ETA. It reads an email thread, identifies a frustrated colleague, and drafts a de-escalating response for your approval. The human's job becomes reviewing, approving, and teaching preferences. Not generating first drafts. Not remembering contexts. Not coordinating logistics. The cognitive labour shifts from execution to judgement.

These five share a common thread. They aren't about AI getting smarter. They're about AI getting embedded: into your devices, your workflows, your relationships with other people's AIs. That's the shift my December predictions missed entirely. I was thinking about capability. The real story is integration.

The Bottom Line

The old regime was prediction: study the technology, model the trajectory, place your bets. The new reality is that prediction itself has become the risk. When a forecast written on 15 December is obsolete by 25 January, the forecast was never the point.

My ten predictions weren't wrong. They were right about the what. They were catastrophically wrong about the when. And in a world moving this fast, wrong about when is just plain wrong.

So here are five new ones, bolder than the last set, informed by the humbling experience of watching careful forecasts expire in real time. I've been doing this long enough to know the smart move would be to hedge again, to add the usual caveat about uncertainty. Instead I'll say this: if these five feel like a stretch to you right now, that feeling is the anchoring bias at work.

If I’m honest, my real hunch is that even these aren’t ambitious enough. Inference costs are on a path to drop by orders of magnitude. Regular architectural progress plus wider inference chip adoption will see to that. Heavy OpenClaw users already report spending $100 or more per day running Opus 4.5 through their personal agents. Now imagine that same capability for a handful (fistful?) of dollars, with ten times the agent power. That’s entirely plausible before December. And at that point, the economics of agent swarms change completely. Not incrementally. Structurally. Something resembling a ‘hard takeoff’ stops being a thought experiment and starts looking like a planning assumption. From where I’m sitting in January 2026 (okay February when you read this), that possibility is looking increasingly difficult to dismiss.

Until next time, you'll find me checking whether February has made these obsolete too.

Comments